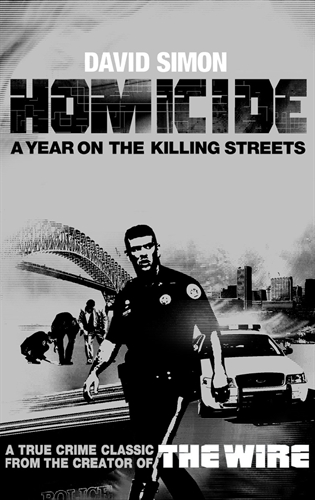

David Simon, later creator of The Wire, at the age of 28 had the chance to shadow the Baltimore Police Department Homicide Unit for the full year of 1988. A Year on the Killing Streets, considered by many as the best book ever written about real police work, is the result of his experiences.

David Simon, later creator of The Wire, at the age of 28 had the chance to shadow the Baltimore Police Department Homicide Unit for the full year of 1988. A Year on the Killing Streets, considered by many as the best book ever written about real police work, is the result of his experiences.The corpse of a sexually abused and strangled 11-eleven year old girl found dumped at a backyard. Tom Pellegrini, the unit's freshman is the prime investigator on the case, which gradually becomes an obsession to him. He is under the wings of Jay Landsman, one of the four squad supervisors, an official mental case with a diseased sense of humour.

A man, while being chased by policemen, was shot dead on the street. By...? In Baltimore, it is not the business of Internal Affairs. The cops have to get their own or find someone else. Terry McLeary has none of it. In January Gene Cassidy, a 28 year old beat cop, was shot in the face twice point blank on the street. Cassidy survived, but has been left blind for the rest of his life. As long as the scum responsible is at large, it's obscene to investigate after one of our own, thinks the stocky Irishman.

Donald Worden, the Big Man, is one of the unit's oldest, most experienced and most respected members who joined the force when it was little more than the strongest gang in the city. He is a natural born detective, respected and trusted even in the black neighbourhood. But times are hard on him this year. His cases are dragging, and along them his - and his team's - stats.

David Brown, the other rookie beside Pellegrini, had the luck and curse of getting the Big Man as his partner. Worden knows that thirty-some years of experience gives him the right to have the rookie jump through hoops for him. For Brown enduring the amused sadism of his elder colleague belongs to the rite of passage as much as proving himself as a detective, so he reluctantly accepts his predicament. And Worden is merciless.

Harry Edgerton, the urbane, jazz-loving black man is an aloof loner without much care for teamwork. His commitment and working ethic is questioned frequently. But not his skills.

Homicide is about real, flesh-and-blood men (and very few women), who crack jokes even over the corpses of murdered children, but who also push themselves to their limits just to catch their killers. They are not above sexist banters, but they always feel a certain type of rage and urge for vengeance when a woman is beaten to death, which is just not there with a male victim. Racism and jaded conclusions based on everyday life are hard to tell apart in a city where ninety percent of murders are black on black. And after the sixth beer in the pub closest to the department, they often contemplate aloud that they are doing the work for God.

The book doesn't offer many new factual insights into the life of a homicide unit or police work. But procedural dramas, with varying level of realism, are as old as television, and virtually anyone can make educated guesses on almost any aspect of that world, in case she manages to correctly recall a relevant episode. What make it unique are the style and the breadth. Simon is a terrific writer. He digs into the dirt of life and finds poetry in it. He captures the frustration of department politics, incessant fight with statistics, the sleepless nightshifts, constant banters, morbid jokes, mundane, everyday killings and cases that silence even people like Landsman. From morgues to press releases it covers the whole gamut of homicide detective work. After reading this 600-page long tome, we close the book with the impression that there is not much more left to say about the subject.

I always put a premium on the books you recommend, especially so when our interests intersect.

ReplyDeleteI hesitated on this one because somehow I expected it to be dry, but boy was I ever so wrong. Thanks for the recommendation, it's a true masterpiece.